Keeping plants free from damage and healthy is always the aim. Yet with more volatile weather, less conventional crop protection products in our armoury and a welcome shift of focus to the health of our soils and the environment, it’s now more important than ever to understand the behaviours of the plant.

Helping plants to help themselves is crucial to high yielding, healthy crops, but how important are the genetics of plants, and what impact does the way we treat them today, have on future inherited characteristics? John Haywood at Unium Bioscience considers the role plant genetics play in the health of our crops now and in future…

From my studies as a human nutritionist, we learned from Doctor Francis M Pottenger Jr, who was a doctor of human medicine, about the quality of the food we eat and its implications on the health of current and subsequent generations.

He famously carried out the “Pottenger Cats” Study, from 1932-1942, examining over 900 cats in multiple generations.

The most important lesson from Pottenger’s cat studies was that the most profound physical degeneration occurred not in the first generation of malnourished cats, but in the next two. (Arguably the same intergenerational patterns of degeneration can be seen in today’s human population):

• Structural deformities, degenerative disease

• Social and psychological disorders, increased aggression, laziness etc

• Reproductive problems

• Increased susceptibility to disease and parasites

It took Dr Pottenger’s study a further four generations, for the cats to return to normal when returned to a healthy diet.

The key lesson we learn from Pottenger’s cats, is that we can impact how our genes are expressed with the nutrition we eat.

Epigenetics is the science of phenotype modification through non-alteration of genes (i.e. nutrition/stress/disease etc).

My question is – does the same occur in plants?

Do crops grown under nutritional stress produce seed which:

- Has lower vigour?

- Produces a poorer stand?

- Has increased susceptibility to disease and insects?

- Has a reduced structural strength, poorer root structures and stem structures with higher lodging potential?

- Possesses a reduced genetic potential in terms of yield and quality?

If we are importing seed to the farm, should we know the nutritional background so we know what limitations it was grown under and what that might impact when we grow it in our soils?

If we are keeping our own grain, we need to maximise the seed size and minimise any potential nutritional deficiencies based on our soil type, agronomy and growing season.

We then need to look at other husbandry techniques and consider their implications on our agronomy such as the impact that azole seed treatments have on Gibberellin Biosynthesis (GA3) – Gibberellic Acid Speeds Up Seed Germination. Gibberellic acid is a natural plant hormone that can be used to speed up the germination of seeds. It is mostly used on seed that is difficult to germinate or ones that takes a long time to germinate.

So, if you selectively inhibit GA, you slow germination, reduce root growth, which causes slower coleoptile emergence, and equals more biotic and abiotic stress risk at a key time of crop establishment.

Rademacher (BASF 2000), Kane&Smiley (1983) reported on root and shoot growth inhibition and potential links to disease expression with azole materials.

GRDC also warns that certain growth retarding fungicide seed treatments can cause “silly seedling syndrome” and coleoptile growth can be further compromised when followed with dinitroaniline herbicides (pendimethalin, trifluralin etc).

The below is standard advice on conventional seed dressings:

Cautions about using fungicide seed dressings

Read and follow directions on fungicide labels carefully.

In some situations, certain fungicide seed dressings may reduce coleoptile length, which could lead to ‘silly seedling syndrome’ (leaves grow under soil surface but don’t emerge), particularly if short coleoptile varieties or deep sowing are used.

Check chemical labels for this information. Coleoptile shortening may also result from use of dinotroaniline herbicides (trifluralin, pendimethalin, oryzalin). Take care where coleoptile-shortening seed dressings are used together with these herbicides, particularly where it is difficult to obtain good depth control of herbicide incorporation and seed placement, such as in sandy soils.

GRDC 2020

Why biologicals are more beneficial

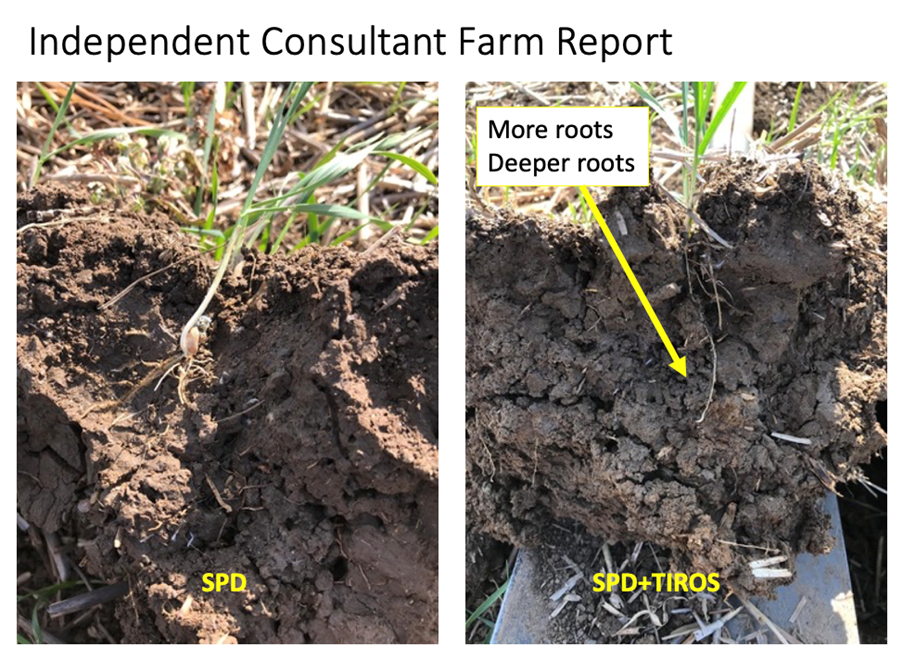

The implications of this guidance, alongside environment, cultivation etc can have consequences for crop establishment and one advantage of the endophytes in the Unium Bioscience’s seed treatment, TIROS, is the ability to reduce these impacts and ensure the crop prioritises resource to where it is most needed, often this is into root growth ahead of shoot growth.

We saw this earlier, thanks to a keen-eyed Green Crop Farmer, who sent in these images.

Upon establishment, it became clear the impact of the endophytes in TIROS – in this case they had prioritised root growth ahead of shoot growth.

A key point when examining the effects of seed treatments is to look at the root system in terms of root quantity, architecture, length and the overall crop establishment.

Needless to say, with other products e.g. Vibrance Duo and also more biologically active soils – no / min till, the reverse is the case with crops emerging very rapidly.

So, I think now we have to revisit how we assess seed treatments and examine their benefits, but like we have always said, look below ground to make the best judgement.

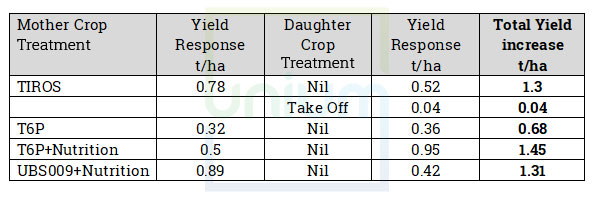

Unium has been looking at this for several years – not in sufficient detail to answer all the questions prompted above but in a high overview level to look at the impact of “mother crop inputs” on the daughter crop.

Here is an overview of the results so far:

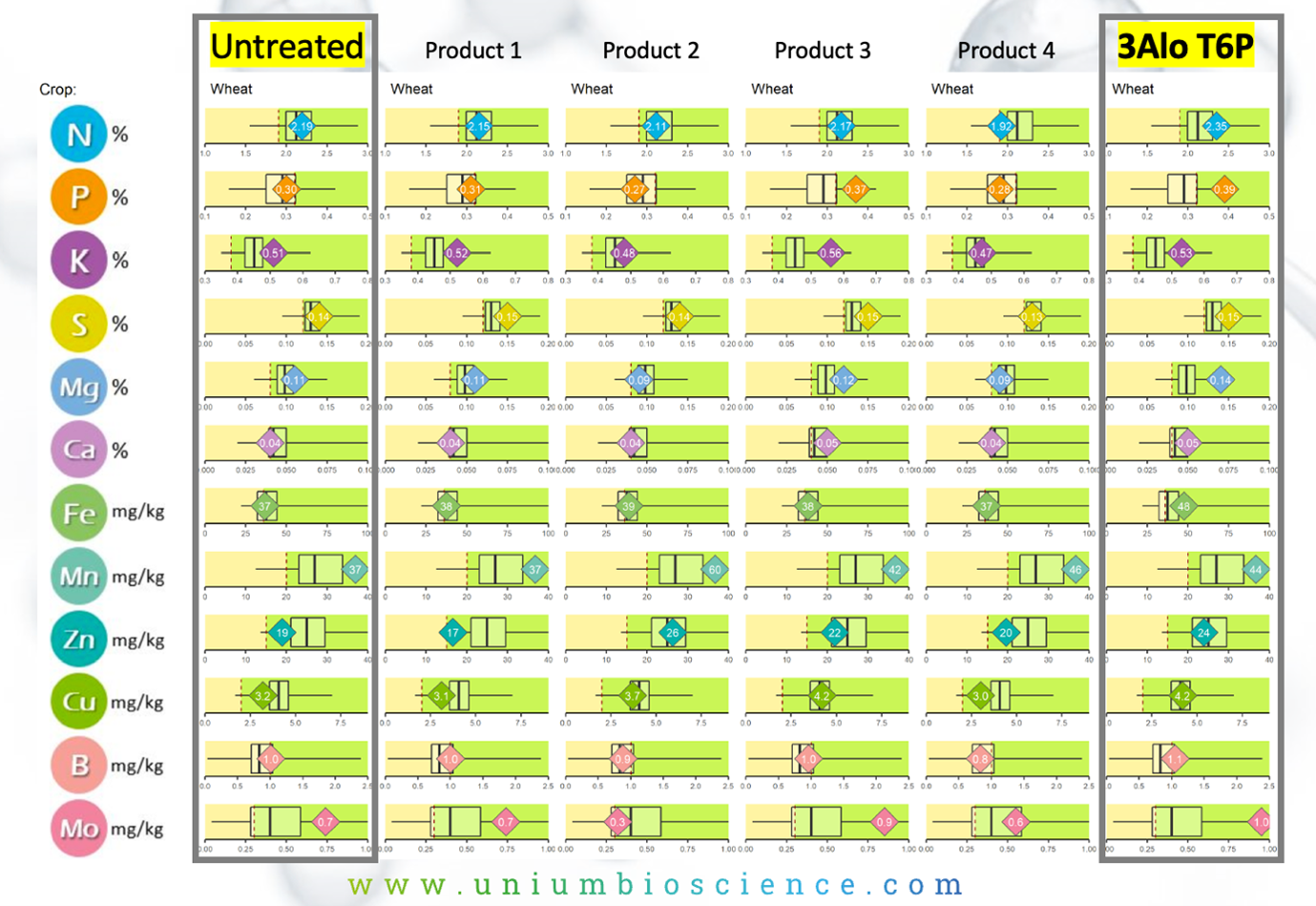

Last year we screened 12 metabolites. This year we have rationalised to 5 for more detailed evaluation along with 13 new seed treatment molecules.

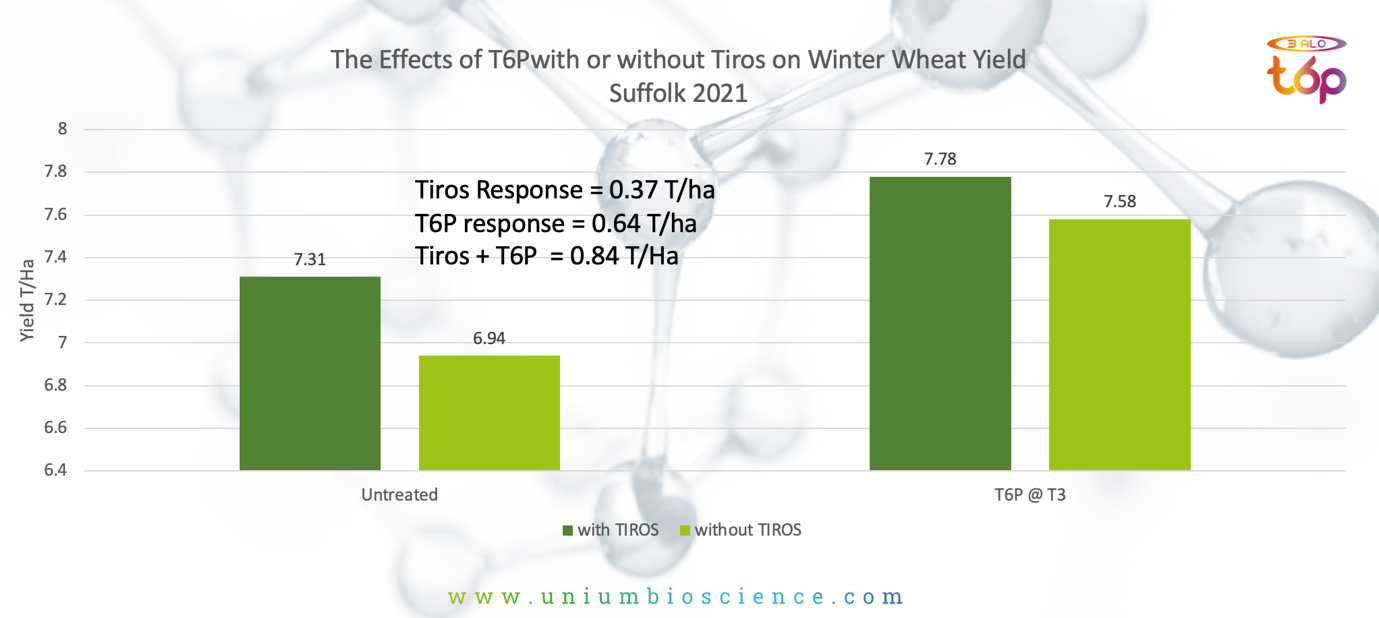

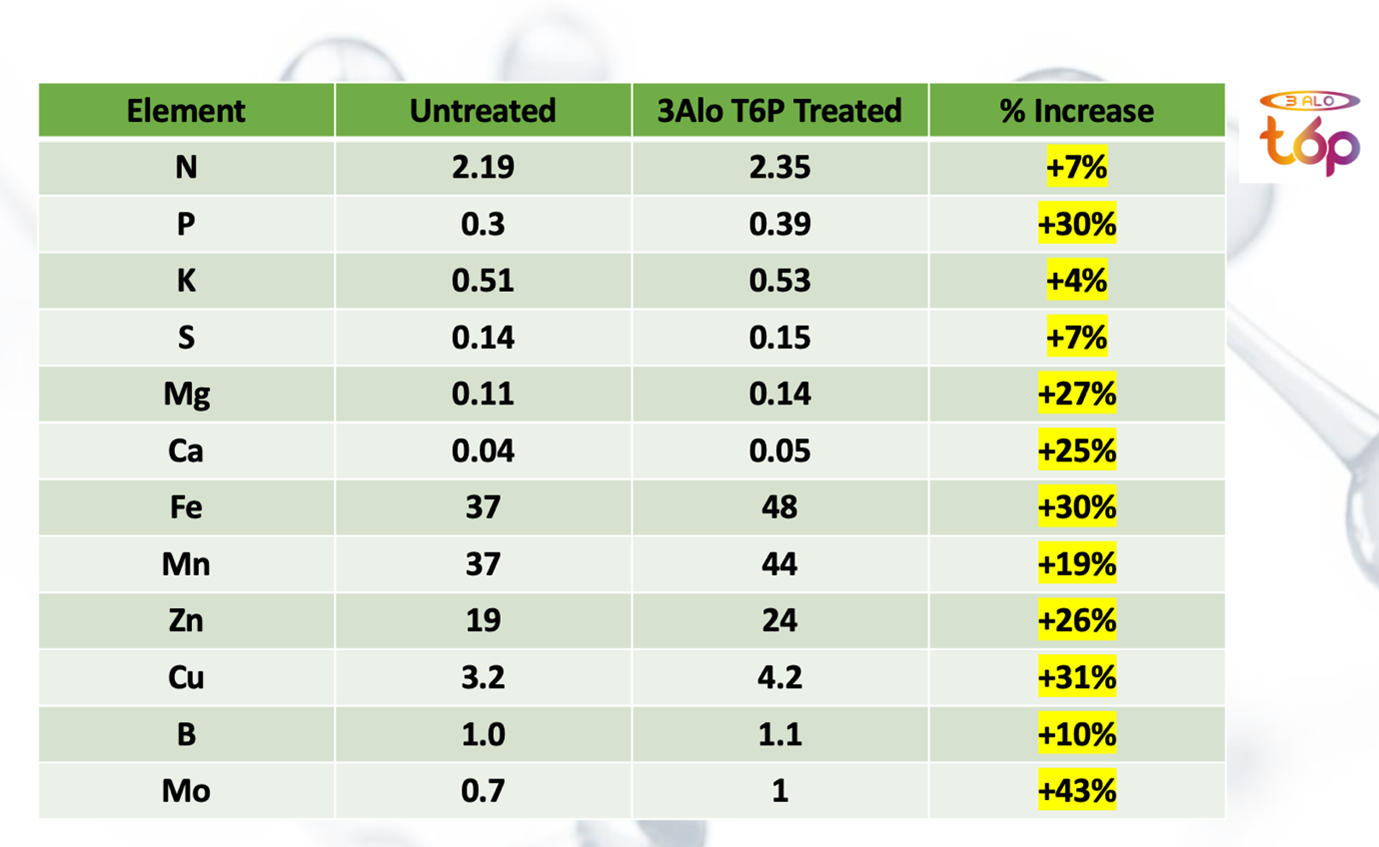

Our focus now is very much on the enhanced nutrient density produced using T6P on the “mother” crop and how it affects the subsequent crop – with better, quicker and more even establishment and increased yield performance. Which is a major step forward in seed production terms whether commercial or farm saved.

So, I think this really is an exciting development in looking at the genetics, the nutrition, soil biological and applied biology to maximise not only the current crop but the following seed crop.

As we move into a new era with greater adoption of biologicals and biostimulants, signalling molecules, soil regeneration, carbon fixation etc, we have to start thinking more consequentially as these systems tend to be more affected than conventional chemistry.

The integration of biologicals into conventional cultural practices requires attention to be given to optimise their performance, we need to ask ‘what else do I need to consider when I make this decision?’ rather than it previously being a binary decision – do I need to apply this to control that… it’s a more complex world but a very exciting and challenging one.

The data below shows the link between the biological supply of nitrogen with Tiros / Tarbis and its subsequent enhanced assimilation with Twoxo later in the season which is then followed with increased utilisation using T6P. This joining of the dots will lead to increased responses and improved reliability from these technologies.